Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

History of Feminism

Related: About this forumwomen and prison reform

Next in a series of women's contributions to historical social reform movements. ![]()

Elizabeth Fry

Elizabeth (Betsy) Fry (21 May 1780 – 12 October 1845), née Gurney, was an English prison reformer, social reformer and, as a Quaker, a Christian philanthropist. She has sometimes been referred to as the "angel of prisons".

Fry was a major driving force behind new legislation to make the treatment of prisoners more humane, and she was supported in her efforts by the reigning monarch. Since 2001, she has been depicted on the Bank of England £5 note.

Fry was a major driving force behind new legislation to make the treatment of prisoners more humane, and she was supported in her efforts by the reigning monarch. Since 2001, she has been depicted on the Bank of England £5 note.

I actually had no idea Fry was that long ago. That is a very early example of social reform, and of a woman's involvement in it.

In Canada, we have the John Howard Society and the Elizabeth Fry Society, for men and women, respectively, involved in the criminal justice system. When I was in law school -- back in the early 70s, before the days of legal aid clinics and when duty counsel in the courts were just starting -- I worked with the local E Fry chapter and ran a program that had volunteers attending assignment court to reach out to women appearing on criminal charges to make sure they had counsel and identify any other supports they needed. My feminist law student sisters at the time weren't much interested in that kind of grunt work in the trenches; they had careers to think of. (Hey, I can, um, bitch about second-wave feminists too.)

E Fry today is an overtly feminist organization. It was founded in Canada in 1939 by Agnes Macphail, a member of Parliament for the Progressive Party, which is one of the groups that eventually morphed into my current party, the New Democratic Party. She was elected in 1921 as Canada's first female MP. Macpahil needs a thread of her own.

But back to Betsy:

At the age of 18, young Elizabeth was deeply moved by the preaching of William Savery, an American Quaker. Motivated by his words, she took an interest in the poor, the sick, and the prisoners. She collected old clothes for the poor, visited those who were sick in her neighbourhood, and started a Sunday school in the summer house to teach children to read.

Sunday School was the only education available to most children in England in the early 1800s, as the children of the poor worked the same hours and days as their parents, in agriculture, in domestic service, as apprentices, and of course later in the mills. The Quakers were active in adult education later in the century; I have a photo from the 1890s of my great-grandfather in Nottinghamshire with a class-sized group of men beside a sign saying something about a Quaker adult ed class, although I can't imagine he was not literate as his family was fairly prosperous, and he wasn't a Quaker.

This would be about 1812:

Prompted by a family friend, Stephen Grellet, Fry visited Newgate prison. The conditions she saw there horrified her. The women's section was overcrowded with women and children, some of whom had not even received a trial. They did their own cooking and washing in the small cells in which they slept on straw. Elizabeth Fry wrote in the book Prisons in Scotland and the North of England that she actually stayed the nights in some of the prisons and invited nobility to come and stay and see for themselves the conditions prisoners lived in. Her kindness helped her gain the friendship of the prisoners and they began to try to improve their conditions for themselves.

... In 1817 she helped found the Association for the Reformation of the Female Prisoners in Newgate. This led to the eventual creation of the British Ladies' Society for Promoting the Reformation of Female Prisoners, widely described by biographers and historians as constituting the first "nationwide" women's organization in Britain.

Thomas Fowell Buxton, Fry's brother-in-law, was elected to Parliament for Weymouth and began to promote her work among his fellow MPs. In 1818 Fry gave evidence to a House of Commons committee on the conditions prevalent in British prisons, becoming the first woman to present evidence in Parliament.

... In 1817 she helped found the Association for the Reformation of the Female Prisoners in Newgate. This led to the eventual creation of the British Ladies' Society for Promoting the Reformation of Female Prisoners, widely described by biographers and historians as constituting the first "nationwide" women's organization in Britain.

Thomas Fowell Buxton, Fry's brother-in-law, was elected to Parliament for Weymouth and began to promote her work among his fellow MPs. In 1818 Fry gave evidence to a House of Commons committee on the conditions prevalent in British prisons, becoming the first woman to present evidence in Parliament.

These early women social reformers were obviously passionate and totally committed to their causes. Fry also managed to have 11 kids between 1804 and 1822, all but one of whom survived childhood.

And of course, there were critics ...

Some people criticized her for having such an influential role as a woman. Others alleged that she was neglecting her duties as a wife and mother in order to conduct her humanitarian work. One admirer was Queen Victoria, who granted her an audience a few times and contributed money to her cause. Another admirer was Robert Peel who passed several acts to further her cause including the Gaols Act 1823 (unfortunately this act did not have much enforcement as most laws of this kind were at the time)

(Peel is credited with establishing the first regular police force, "bobbies".)

I wonder whether having a woman on the throne from 1837 to 1901 contributed to women finding a voice in Victorian England.

Elizabeth Fry also helped the homeless, establishing a "nightly shelter" in London after seeing the body of a young boy in the winter of 1819/1820. In 1824, during a visit to Brighton, she instituted the Brighton District Visiting Society. The society arranged for volunteers to visit the homes of the poor and provide help and comfort to them. The plan was successful and was duplicated in other districts and towns across Britain.

The US has a woman prison reformer of almost equal renown, I think?

InfoView thread info, including edit history

TrashPut this thread in your Trash Can (My DU » Trash Can)

BookmarkAdd this thread to your Bookmarks (My DU » Bookmarks)

2 replies, 4121 views

ShareGet links to this post and/or share on social media

AlertAlert this post for a rule violation

PowersThere are no powers you can use on this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

ReplyReply to this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

Rec (0)

ReplyReply to this post

2 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

women and prison reform (Original Post)

iverglas

Apr 2012

OP

iverglas

(38,549 posts)1. perhaps not equal renown ...

but googling for united states prison reform 19th century woman, I found

http://reformproject.wikispaces.com/prison_reform_19th_century

Dorothea Dix

Dorothea Dix was first introduced to prison reform when she went to England to recover from tuberculosis. When she returned to the United States in the 1840's, she was so inspired by what she had seen in England that she began to help inmates who were mentally ill in the United States. She believed these inmates deserved better treatment than they were being given. Serving for the Union, she had helped the mentally ill during the Civil War. Because she thought that the mentally ill were so mistreated, she took matters to the courts and won. After this, she visited jails and almhouses, to take notes for a document she drafted and gave to the Massachusetts legislature. This document won her support and caused funds to be set aside for the expansion of the Worcester State Hospital. In addition, she helped to found thirty-two mental hospitals, a school for the blind, and many nursing training facilities. The women under her nursing training struggled to be accepted by army physicians who felt that they, the males, should be in charge of medical issues. She was strict in her criteria for women that she would train, and she was very impatient. For this, she lost the support of the United States Sanitary Commission and other groups that had helped her begin her training. She had a difficult time being accepted, but Dorothea Dix was determined to help.

Dorothea Dix was first introduced to prison reform when she went to England to recover from tuberculosis. When she returned to the United States in the 1840's, she was so inspired by what she had seen in England that she began to help inmates who were mentally ill in the United States. She believed these inmates deserved better treatment than they were being given. Serving for the Union, she had helped the mentally ill during the Civil War. Because she thought that the mentally ill were so mistreated, she took matters to the courts and won. After this, she visited jails and almhouses, to take notes for a document she drafted and gave to the Massachusetts legislature. This document won her support and caused funds to be set aside for the expansion of the Worcester State Hospital. In addition, she helped to found thirty-two mental hospitals, a school for the blind, and many nursing training facilities. The women under her nursing training struggled to be accepted by army physicians who felt that they, the males, should be in charge of medical issues. She was strict in her criteria for women that she would train, and she was very impatient. For this, she lost the support of the United States Sanitary Commission and other groups that had helped her begin her training. She had a difficult time being accepted, but Dorothea Dix was determined to help.

And the other US prison reformer noted there:

Eliza Farnham

Eliza Farnham was appointed prison matron of Sing Sing Prison in 1844. She believed strongly in prison reform, but faced a lot of obstacles. Previously, Sing Sing Prison had been the quintessential scary "House of Fear" under several wardens, most notably Elam Lynds. A new board of inspectors, helmed by John Worth Edmonds, wanted to reform the prison and ergo appointed Eliza Farnham, a well-known philanthropist, feminist, phrenologist, and author. Farnham removed the silence rule, added an educational program, and advocated such luxuries as decorations, recreational activities, and leisure activities. Eventually, Farnham angered John Luckey, a chaplain, and their disagreements prompted Farnham to leave Sing Sing in 1877. But Farnham was remembered for her work as a prison reformist.

Eliza Farnham was appointed prison matron of Sing Sing Prison in 1844. She believed strongly in prison reform, but faced a lot of obstacles. Previously, Sing Sing Prison had been the quintessential scary "House of Fear" under several wardens, most notably Elam Lynds. A new board of inspectors, helmed by John Worth Edmonds, wanted to reform the prison and ergo appointed Eliza Farnham, a well-known philanthropist, feminist, phrenologist, and author. Farnham removed the silence rule, added an educational program, and advocated such luxuries as decorations, recreational activities, and leisure activities. Eventually, Farnham angered John Luckey, a chaplain, and their disagreements prompted Farnham to leave Sing Sing in 1877. But Farnham was remembered for her work as a prison reformist.

Dorothea Dix

In 1831 she established in Boston a model school for girls, and conducted this successfully until 1836, when her health again failed.[2] In hopes of a cure, in 1836 she traveled to England, where she had the good fortune to meet the Rathbone family, who invited her to spend a year as their guest at Greenbank, their ancestral mansion in Liverpool. The Rathbones were Quakers and prominent social reformers, and at Greenbank, Dix met men and women who believed that government should play a direct, active role in social welfare. She was also exposed to the British lunacy reform movement, whose methods involved detailed investigations of madhouses and asylums, the results of which were published in reports to the House of Commons.

After she returned to America, in 1840-41, Dix conducted a statewide investigation of how her home state of Massachusetts cared for the insane poor. In most cases, towns contracted with local individuals to care for people with mental disorders who could not care for themselves, and who lacked family and friends to provide for them. Unregulated and underfunded, this system produced widespread abuse. After her survey, Dix published the results in a fiery report, a Memorial, to the state legislature. "I proceed, Gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of Insane Persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience." The outcome of her lobbying was a bill to expand the state's mental hospital in Worcester.

After she returned to America, in 1840-41, Dix conducted a statewide investigation of how her home state of Massachusetts cared for the insane poor. In most cases, towns contracted with local individuals to care for people with mental disorders who could not care for themselves, and who lacked family and friends to provide for them. Unregulated and underfunded, this system produced widespread abuse. After her survey, Dix published the results in a fiery report, a Memorial, to the state legislature. "I proceed, Gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of Insane Persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience." The outcome of her lobbying was a bill to expand the state's mental hospital in Worcester.

She was a multi-tasker. She was Superintendent of Army Nurses for the Union Army, kind of the Florence Nightingale of the US.

Eliza Farnham

Eliza Farnham (November 17, 1815 – December 15, 1864) was a 19th-century American novelist, feminist, abolitionist, and activist for prison reform.

In 1844, through the influence of Horace Greeley and other reformers, she was appointed matron of the women's ward at Sing Sing Prison. She strongly believed in the use of phrenology to treat prisoners. She also advocated using music and kindness in the rehabilitation of female prisoners. She retained the office of matron until 1848, when she moved to Boston, and was for several months connected with the management of the Institution for the Blind.

In 1849 she visited California, and remained there until 1856, when she returned to New York. For the two years following, she devoted herself to the study of medicine, and in 1859 organized a society to assist destitute women in finding homes in the west, taking charge in person of several companies of this class of emigrants. She subsequently returned to California.

She died from consumption in New York City at the age of 49.

In 1844, through the influence of Horace Greeley and other reformers, she was appointed matron of the women's ward at Sing Sing Prison. She strongly believed in the use of phrenology to treat prisoners. She also advocated using music and kindness in the rehabilitation of female prisoners. She retained the office of matron until 1848, when she moved to Boston, and was for several months connected with the management of the Institution for the Blind.

In 1849 she visited California, and remained there until 1856, when she returned to New York. For the two years following, she devoted herself to the study of medicine, and in 1859 organized a society to assist destitute women in finding homes in the west, taking charge in person of several companies of this class of emigrants. She subsequently returned to California.

She died from consumption in New York City at the age of 49.

She seems to be a bit of an unsung heroine.

There's a lot of hers stories out there.

And of course, animal welfare was among the social reform causes these well-rounded women espoused:

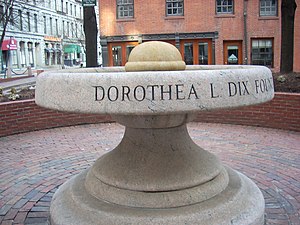

Fountain for thirsty horses Dix gave to

the city of Boston to honor the MSPCA

iverglas

(38,549 posts)2. Australian angles

There's one to Elizabeth Fry as well -- and she also multi-tasked into the field of nursing and the care of mental patients, it seems:

http://womenshistory.about.com/od/reformmore/p/elizabeth_fry.htm

While Elizabeth Fry is known more for her prison reform activities, she was also active in investigating and proposing reforms for mental asylums. For more than 25 years, she visited every convict ship leaving for Australia, and promoted reform of the convict ship system. She worked for nursing standards and established a nursing school which influenced her distant relative, Florence Nightingale. She worked for the education of working women, for better housing for the poor including hostels for the homeless, and she founded soup kitchens.

http://www2.gol.com/users/quakers/fry.htm

One area where she made important changes was in the treatment of prisoners sentenced to transportation to the colonies. One day in 1818 when she visited the prison she found some of the prisoners were about to riot because the next day they would be taken in 'irons' (hand- and ankle-cuffs and chains), on open wagons, to the ships that would carry them to Australia. Elizabeth Fry arranged for them to be taken in closed carriages to protect them from the stones and jeers of the crowds, and promised to go with them to the docks. In the five weeks before the ships actually sailed, the ladies of the Association visited daily, and provided each prisoner with a 'useful bag' of things the prisoners would need. They made patchwork quilts on the voyage, which were sold on arrival to provide some income. During the next twenty years she regularly visited the convict ships: in all 106 came under her care.

Huh!

There's a really comprehensive timeline of Australian prison reform movements here:

http://justiceaction.org.au/cms/about/history-of-the-prisoner-movement

Obviously the Australian situation is unique, since the earliest European settlers were prisoners themselves.

How about it, Australian cousin? Women and social reform movements in Australia?

edit -- googling Australia "social reform" women finds gazillions of them. Thread-worthy in themselves!

Anybody who thinks that women in history are properly accounted for in history lessons isn't paying attention, I think. Of course, one reason for their exclusion is the lack of attention paid to social reform and reformers and the problems they were attacking, generally ...