Science

Related: About this forumResearchers suggest another ancestry for Native Americans (Boston Globe)

By Virgie Hoban GLOBE CORRESPONDENT JULY 21, 2015

It has long been thought that the founders of the Americas, who traversed a frozen ice bridge across the Bering Strait 15,000 years ago, carried with them a uniform ancestry rooted in Eurasia.

But a Harvard Medical School study published Tuesday in the journal Nature upends that theory, concluding that some modern-day Brazilians in the Amazon carry traces of DNA that suggest they share a history with indigenous Australians. That finding suggests the founding population of the Americas was more diverse than suspected and arrived in separate waves.

“We found this pattern in the genetic data and were kind of very surprised and incredulous,” said David Reich, a Harvard geneticist and coauthor of the study.

The study left other questions unanswered, most prominently when and how the distant cousins reached South America.

A separate study published in the journal Science also detected traces of DNA harking to Australia, New Guinea, and other parts of Australasia in South Americans, but those researchers say that mixing is a more recent phenomenon and that there was a single burst of migration.

***

more: https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2015/07/21/harvard-study-sheds-new-light-origin-native-american-populations/NTs5hr06ffoq8cWM0T3BGN/story.html

Not linking to Science or Nature articles, since both journals have really sucky Web sites now.

malthaussen

(17,200 posts)...but it's not impossible to imagine some unfortunate mariners washing up on the shore of South America. What's the DNA of the Easter Islanders like, I wonder.

-- Mal

BlueMTexpat

(15,369 posts)Turin_C3PO

(13,998 posts)I also wouldn't be surprised if some of the northeastern tribes have some archaic European DNA in them.

starroute

(12,977 posts)But of course it always gets dismissed as the result of recent admixture. It would take detailed studies to determine if, say, any of it was of a particularly archaic type that's no longer found in Europe.

Leith

(7,809 posts)There are several distinct language families that are as different from each other as Chinese is from English. If native Americans are one big ethnic group (which doesn't really seem plausible), how did the diverse languages arise? And are there any that seem to have a distant kinship with Asian or Australasian languages?

eppur_se_muova

(36,263 posts)not my area of specialty, but I get the impression that NA linguistic history is even more hotly debated than NA origins. See, e.g., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indigenous_languages_of_the_Americas#Origins

I'm not expecting any simple answers to this puzzle.

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

- Hamlet (1.5.167-8), Hamlet to Horatio

DeadEyeDyck

(1,504 posts)That's got to count for something.

Igel

(35,317 posts)Take Spanish, French, Portuguese, Italian, Romanian. They split up at perhaps 400 AD. They're obviously related.

Russian, Serbian, Polish, Czech are the same--they broke up perhaps 800 AD. Germanic languages broke up earlier, maybe 1 AD. Dates are approximate and possibly 20 years out of date.

You reconstruction the Romance languages to Italon, Slavic to Proto-Slavic, Germanic to Proto-Germanic. You can pitch in Classical Greek at that point, Sanskrit, and you find that they're related.

But every century each language loses words that link it with the others. Every few hundred years sound changes make the comparison harder. We use the oldest available language data we can--so Latin, Attic Greek, Old Church Slavic, Classical Armenian, Sanskrit.

Armenian is weird. So's Albanian. It took a long time to spot that they're related to the others. I mean, most Indo-European languages have a word like *dwo for "two"--duo, dos, dva, two. Classical Armenian has erku. Figuring out how, by consistently applied sound changes, *duo > erku was a mess, but the problem was solved. It's likely they were all closely related dialects at around 4000 BC. Give or take.

Some managed to find a set of words that link Turkic languages, Indo-European, Semitic, Altatic and some other language families. But that's a tough call, because they've each had 6000 years to lose common data, and the reconstruction for Nostratic is at about 8-10k years ago. That's a long time to lose common features and words. What's left is less and less until you're finally down to roots of 2-3 letters, and some doubt there's enough left to consider. If you look at the set of sounds and their random occurrence over the proto-languages, the set of words left is just about the same number of words you'd get by coincidence.

Ruhlen, Greenberg, and others think you can do a mass comparison and get back far beyond 10k years. The difficulty is that some segments, like initial m-, are very stable. Once a word starts with m-, it's going to stick there until the word goes away. Other words are similar to the sounds their meanings have. So smacking your lips and "mama" (mommy) and "mammae" (breasts). And babies "grow" sounds in a specific order: m- is one of the first a baby gets. So her first word is probably "mama." This means as you lose similarities over time, those last three traits become more and more important. At that point, the "random chance" bit from the last paragraph is no longer "mostly." It's random chance + some predicted, expected skewness.

By 10k years ago, it's unlikely that we'd spot any connection between languages.

What's worse is that I personally find the argument compelling that language isolation produces bizarre changes. Andersen looking at some varieties of Romansch (a daughter of Latin) pointed out some oddball changes. Caucasian languages are isolated. Khoei-San languages were isolated. And in the Americans, a sparse population would be isolated.

It's also the case that if you don't want to be like another group your languages push apart. So in Guatemala the change between two close dialects of one language a couple of miles away in 1920s diverged more than expected by the 1990s--in the 1920s there was some feud that started and even though both villages have physically grown and their borders are close their speech is diverging. American "black English" has changed more quickly since the late 1950s than it did in the previous 150 years; many of its traits were much more Southern English in 1820 than now. Under conditions of slavery, the two varieties weren't that different; under Jim Crow, not much change. But as "the melting pot" changed and ethnic pride/identity/nationalism surged, it started to diverge much more quickly--standard English stopped being something to be like and started to be something to be different from. The same happens in high school: Most kids within a community start a given high school speaking the same language, but by the end of their freshmen year jocks, nerds, geeks, whatever the groupings are, each have their own identifiable and distinct speech variety. Vowels move, intonation changes, there are different distributions of words.

It's likely that not only were some tribes isolated in the early Americas, but others pushed away linguistically (even as others grew closer together).

The latest settlement date for the Americas is around 15,000 years ago. When you see large swathes of a continent speaking languages that are obviously related, you're looking at a huge expansion in the last 6-8000 years. That could be from war and genocide or assimilation, disease wiping out tribes, or maybe drought and famine caused an area to be evacuated.

BTW, English and Chinese are both, by those who think we can reconstruct back 10k years or so, Nostratic. So they're different, but the time depth separating them isn't as much as we'd expect some Native American languages to diverse. There are a limited variety of human languages, believe it or not, and languages tend to cycle through the various types. Proto-Indo-European, early one, was probably monosyllabic and tonal, much like Chinese. (Meanwhile, we can reconstruct Chinese back to an earlier version in which words were longer and with fewer tones.)

eppur_se_muova

(36,263 posts)I've always found the topic interesting, despite being a mediocre language learner. I wish comparative linguistics were offered as a college course as commonly as introductory foreign languages were ! Do courses in French I-II etc. do as much good as a course providing an overview of all the languages of the world ? There's room for both, as they serve different purposes, but I wish the latter were more of a mainstream educational option.

I read this book in grad school (chemistry, not linguistics) and thought it fascinating, but didn't wed myself to any of its conclusions, as the field is obviously in a state of flux, and probably will be forever: https://archive.org/stream/189942876InSearchOfTheIndoEuropeansJPMallory/189942876-In-Search-of-the-Indo-Europeans-J-P-Mallory_djvu.txt It's kind of a blend of linguistics, history, and archaeology, as it attempts to locate the physical homeland of the first speakers of an Indo-European language.

I once read a book on the Chinese language which explained the process of change by which completely different monosyllabic Chinese words evolved from each other -- a vowel in the middle might change, a few centuries later a consonant might be dropped from the end, only to be replaced by a different consonant a few centuries later, and the consonant at the beginning dropped -- let such processes go on for a while, and pretty soon "Fred" becomes "Axlotl". All of this takes place at different, seemingly capricious times for different words, and so the language slowly shifts; there's no organized or systematic process involved. Add that most speakers of the language are illiterate AND that the writing system isn't phonetic anyway, and shift happens. So it's hardly surprising that NA languages would have diverged so widely, if they were only given time. It seems to me that languages of the Americas are somewhat unique in one respect: they may share a common origin at a common time, with no subsequent influence from other, outside language groups for millenia. Perhaps, say, the native languages of Australia are similar; I don't know. But that may mean some of the relationships among NA languages are less ramified than among Old World languages; perhaps we can "see farther back" in such a situation, and so we see phenomena that are obscured in Old World languages by the sheer number of various influences.

Now I'm going to look up "Italon" and "Nostratic" -- I'd never heard of either term before. ![]()

(BTW, is "Altatic" supposed to be "Altaic"?)

cstanleytech

(26,293 posts)to adapt and learn the local language rather than keep their own just as a matter of long term survival.

muriel_volestrangler

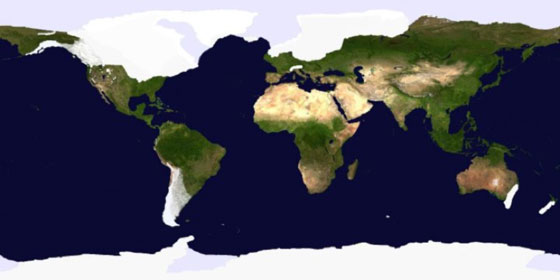

(101,320 posts)Really? There was an ice sheet, 15,000 years ago, covering much of South America, over the equator, and it had been joined to that in North America, so that Central America had an ice sheet on it too? Sound unlikely to me. This looks a fairly typical map of ice in the last glacial period:

There's a few thousand miles between the ice sheets there, and I don't think they were ever linked.

ismnotwasm

(41,986 posts)Fascinating!