Environment & Energy

Related: About this forumGimme that old-time population growth

In discussions of human population growth, I tend to take the view that it's mostly driven by underlying material forces - genetic imperatives, resource accessibility, climate, geography, geophysical history, etc. I usually give short shrift to the notion that culture has much to say about it in the big picture, both because culture tends to be local (I'm an unabashed globalist in this matter) and also because culture seems to me to be more of an effect than a cause in the positive and negative feedback loops that control the various aspects of human growth.

Supporters of indigenous cultures regularly raise the objection that native societies have lived for long periods in balance with their surroundings, showing little sign of growth in numbers. My usual rejoinder is that these examples are accidents of location, exceptions and outliers that do not invalidate my central materialist premise. Needless to say, this rebuttal doesn't go over well with the indigenist crowd.

I recently became aware of the HYDE database. It contains, among other interesting data, a population reconstruction for the last 12,000 years. It seems to be the most detailed and authoritative set of estimates so far. I decided to graph their data for the period 10,000 BCE to Year 0. I chose this period so we could see how population behaved before the advent of the modern influences that are normally implicated in growth: monotheistic religions, capitalism, fossil fuels, and communication/propaganda technology like the printing press.

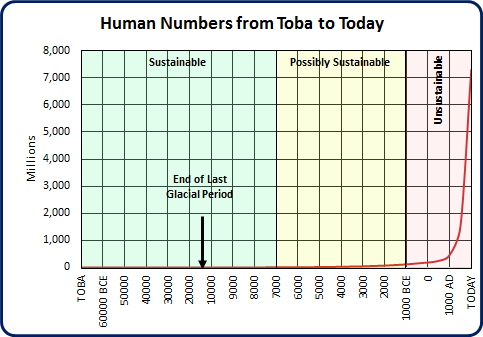

The graph is unambiguous: world population apparently followed an exponential growth curve that was consistent for over 10,000 years (though it does seem to accelerate somewhat as time goes on).

The smoothness of the curve makes me wonder about the reconstruction techniques used for the HYDE data - it seems to imply mathematical interpolation between necessarily imprecise data points. However, it seems clear that an exponential trend has been a feature of human population growth since the very beginning, through the rise and fall of a wide variety of cultures.

Fortunately, since about 1980 global population growth has dropped back from exponential to "merely" linear growth. In my view that deceleration is probably due to issues like overcrowding (possibly leading to the version of Hans Selye's "General Adaptation Syndrome" seen in John Calhoun's "Mouse Utopia" experiments), rising resource costs, declining economic opportunities and rising social instability. However, with our growth still adding 80 million people a year to the planet this is pretty small consolation.

HYDE presents (gridded) time series of population and land use for the last 12,000 years ! It also presents various other indicators such as GDP, value added, livestock, agricultural areas and yields, private consumption, greenhouse gas emissions and industrial production data, but only for the last century.

The HYDE numbers are also given in the Wikipedia article on world population estimates.

SheilaT

(23,156 posts)are experiencing high death rates at all ages, high enough to keep births and deaths in more or less balance. It's not that they were respectful of their environments and deliberately kept their numbers down. Rather, it was the brutal fact of nature that did the trick.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Elders who offer themselves to the wolves when that's needed.

A society that recognizes that the sick and injured should not always be saved.

Young women who say "no", and young men who respect that word.

A culture that lovingly but firmly supports that behavior.

What does it take to bring such a consciousness into a society?

IMO such social consciousness can only emerge when the limits and the consequences of exceeding them are both clearly visible to every member of the society. Whenever the limits are less immediate, growth resumes.

SheilaT

(23,156 posts)nature and the balance thereof. The death rates were high, very high, from all sorts of things.

There's a modern inclination to attribute nobility where none exists in traditional cultures. Humans everywhere have wreaked havoc on the landscape and biosphere. A whole bunch of species went extinct on this continent right after the first humans arrived. Gee. And in historical times, the first inhabitants were known to stampede buffalo over cliffs, killing vastly more than they could consume. In the more ancient world, farming practices created deserts out of once fertile landscapes.

It is not particularly natural to our species to look ahead, to care what destruction we bring about. We are incredibly short-sighted, overall.

Gregorian

(23,867 posts)here's what I've observed: (We're on a fixed geographic area, and absolute numbers are the bottom line.) So for all of eternity, we have essentially been able to live as though resources and land were infinite. The curve, even though it's exponential, resulted in population numbers that were effectively a flat line. There has been no need to address the issue of population. In other words, 100 people can all have 10 children, and not have it affect a thing. But 7 billion people having 3 children suddenly turn this available land, and resources, into an immediate disaster. With respect to geographic area of the globe, we suddenly reached a point where we must address personal responsibility in terms of something we've never had to address. This represents a shift in the human psyche that is foreign to people. This is what I believe we're facing today- the lag between how we've always lived versus how we must live now, or face dire consequences.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Entrenched beliefs tend to be quite impervious to countervailing facts. The majority of people will keep right on on believing that the world is essentially infinite (especially when you factor in human ingenuity) until long after the situation becomes dire. The usual scapegoats will be hauled out to explain the problem and provide a blame shield: meddling governments, overbreeding brown people, apostates, atheists and gays etc. We're seeing practice runs of this already.

Once the limits are obvious to everyone and world population is on its way down through a couple of billion, the beliefs will change.

Too late? Too bad.

pscot

(21,024 posts)a hockey stick. Would the indigenous element include those who think technology is going to pull our nuts out of the fire? Deniers would be indigenous too, I think. Everyone, in fact, who credits all good things to human agency and blames god or bad luck when things go wrong. Or just doesn't care. Calhoun's mouse paradise is a wonderful fable. Calhoun didn't know he was building a behavioral sink. He was utopian in that sense.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)

pscot

(21,024 posts)GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)

The graph begins with the Toba catastrophe and uses an estimate of 20,000 people who survived that bottleneck. Whether that number was tens of thousands more or a few thousand less is immaterial given the time scales involved.

The shaded sustainability periods are my estimates. When our numbers were below 7 million (before 7,000 BCE) Homo sapiens was a sustainable species. As our numbers grew from 7 million to 100 million over the following 6,000 years we became progressively more unsustainable. Since 1000 BCE when our population rose past 100 million, we have IMO been categorically unsustainable. In the last 1,000 years we have entered the explosive overgrowth phase typical of a "plague species".

There is no point arguing about whether the human presence on the planet is sustainable until our total population has again subsided below 100 million. Until that happens, the answer is a categorical "No".

Even then, our species would be unsustainable if the number of births was to rise above the number of deaths. This presents what seems to us to be a moral conundrum around the issue of death. For a very small society that understands that the survival of everyone is in peril if this principle is violated, the moral issues will inevitably be quite different.

muriel_volestrangler

(101,361 posts)In their summary of historical population data (totals, percentages, etc), for instance, they say for regional population at 10,000 BC (ie the dawn of agriculture) that Europe has 22.5% of the world population, and Asia (minus the Middle East, and Asian Russia) 30.4%. Really? Had the much smaller Europe really been that much more productive for hunter-gatherers than the huge Asia? And at that time, again, before agriculture, they estimate the North American population at 39,000, and Latin America at 278,000. Again, really? Given the continent was populated from the north, it seems pretty unlikely that 7/8ths charged straight through to Latin America, before they had crops.

Ah - I just clicked on an individual cell in their spreadsheet; the 10,000 BC North American population is given as 38.8936810143336 thousands. So obviously they are extrapolating from something, which helps explain the nice exponential-like curve they end up with.