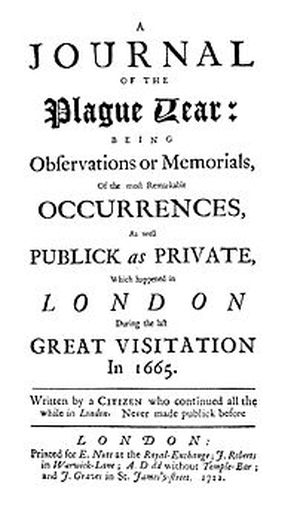

Daniel Defoe: 'A Journal of The Plague Year' London, 1665

Last edited Tue Mar 17, 2020, 05:27 PM - Edit history (2)

'Daniel Defoe: 'A Journal of the Plague Year'. By Dermot Kavanagh, London Fictions. Excerpts, Ed.:

A Journal of the Plague Year is Daniel Defoe’s novel of the Great Plague of London in 1665, published fifty-seven years after the event in 1722. Defoe intended the book as a warning. At the time of publication there was alarm that plague in Marseilles could cross into England. It is a kind of practical handbook of what to do, and more importantly, what to avoid during a deadly outbreak. It is also a haunting, atmospheric portrait of London in the seventeenth century. Rich in detail, naming streets, alleys, churchyards and pubs, it chronicles the chaos of daily life during a dreadful onslaught.

No definitive figure exists for the total number of deaths from the Plague but it is estimated that twenty percent of the populace died as a result. The spirit of the book calls to mind the Blitz era, with its dark East End setting and themes of human distress and fortitude..Defoe collected these bills, and other plague ephemera, which must account for the great amount of detail he brings to the text. But the book reads best as an historical novel that mingles fact and fiction, as Defoe was barely five years old at the time of the events. After the mortality bills, his primary sources were the many contemporaneous accounts produced in the fifty years, or so, afterwards. His genius is to construct a gripping novel filled with detail, statistics, gossip, hearsay and half-remembered stories that is totally convincing...

- Daniel Dafoe (c. 1660- 1731) born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Dafoe has been seen as one of the earliest proponents of the English novel, and he was a prolific and versatile writer of more than 300 works—books, pamphlets, and journals—on diverse topics such as politics, crime, religion, marriage, psychology, and the supernatural..https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Defoe

London had been transformed in the decade before the Plague hit. The austerity of the Interregnum was replaced by the energy and frivolity of the Court of Charles II. People were attracted to the capital as a place of opportunity, fashion was back in favour and entertainment was no longer frowned upon. London was a liberal, dynamic destination. - the wars being over, the armies disbanded, and the royal family and the monarchy being restored…the town was computed to have in it above a hundred thousand people more than it ever held before…All the old soldiers set up trade here…All people were grown gay and luxurious, and the joy of the Restoration had brought a vast many families to London.

The net effect was more people living in crowded and insanitary conditions than ever before, alongside a thriving population of rats, whose fleas carried the plague virus. The outbreak was believed to have started in December 1664 after goods imported from Holland were carried to a house in Long Acre. Initially deaths were few and restricted to the St. Giles and Long Acre areas. By June however, there were signs it had spread to the City and after sixty-eight deaths in St. Giles, the hope it would be short-lived and parochial was shattered: 'Now there died four within the city, one in Wood Street, one in Fenchurch Street and two in Crooked Lane'...

- Coronation portrait of King Charles II crowned at Westminster Abbey on April 23, 1661.

The author, a well-connected city merchant, locates his address with characteristic exactitude: 'I lived without Aldgate, about midway between Aldgate church and Whitechapel Bars, on the left hand or north side of the street'. (Whitechapel Bars marked the eastern boundary of the City’s liberties at the junction of Aldgate High Street, Whitechapel High Street and Petticoat Lane). The six months it took for the virus to establish itself are portrayed as a time of ignorance and denial as a kind of ‘phoney war’ mentality held sway: - people had for a long time a strong belief that the plague would not come to the city, nor into Southwark, nor into Wapping or Ratcliff at all…many removed from the suburbs…into those eastern and south sides as for safety, and, as I verily believe, carried the plague amongst them there.

Low-level fear was exploited and as unease grew, so did the number of street astrologers, wizards and quack doctors. Chancers and opportunists spotted a gap in the market and the streets filled 'with a wicked generation of pretenders…if but a grave fellow in a velvet jacket, a band and a black cloak…was but seen in the streets the people would follow them in crowds'. That London archetype, the quick-witted, fast talking con-man is represented by a 'quacking sort of fellow' who advertises himself as a self-styled expert, diagnosing plague symptoms with the slogan 'he gives his advice to the poor for nothing' in capital letters. After examination he recommends his exclusive ‘remedies’ to the patient for the fee of half a crown, responding to any complaints with the rejoinder 'I give my advice for nothing, but not my physic'. Inevitably, he is nowhere to be seen when the virus manifests itself.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Fire_of_London

Following the example of the Court, which removed to Oxford in May, the wealthiest households fled to their houses in the country, as they did so their servants fearful of being left behind, if taken ill, sought out preventative cures and remedies. Defoe likens the clamour to a type of mass hysteria: 'mad upon their running after quacks and mountebanks…it is incredible how the posts of houses and corners of streets were plastered over with doctor’s bills and papers of ignorant fellows'. As the pace of the infection picked up during the summer months, the physical and psychological toll is graphically imagined. Defoe switches styles between a straightforward re-telling of events and first hand, eye-witness accounts. He vividly describes the suffering the symptoms caused: those spots they called the tokens were really gangrenous spots, or mortified flesh in small knobs as broad as a little silver penny, and as hard as a piece of callous or horn..no instrument could cut them, so that many died roaring mad with the torment...With the virus tightening its grip and the death toll soaring, the author is forced to stay close to home. He observes what happens in his immediate locality, the triangle between Aldgate, Petticoat Lane and Houndsditch. A powerful sense of place is created in a claustrophobic, twilight world of rookeries and alleyways...

- St. Botolph's Aldgate, rebuilt 1740s.

Read More, https://www.londonfictions.com/daniel-defoe-a-journal-of-the-plague-year.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Plague_of_London

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Journal_of_the_Plague_Year

MFM008

(19,814 posts)The great fire of 1666 cleaned it all up.....

appalachiablue

(41,144 posts)occurred in Sept. 1666 and the rebuilding of London by Wren and others came afterwards. ~ Glad my ancestors left for the colonies by 1664 although they were basically from south England not London I'm fairly sure. What a time then.

- (Wiki) Great Fire of London, 1666: Origin and consequences of the fire

The Great Fire started at the bakery (or baker's house) of Thomas Farriner (or Farynor) on Pudding Lane shortly after midnight on Sunday, 2 September, and spread rapidly west across the City of London. The major firefighting technique of the time was to create firebreaks by means of demolition; this was critically delayed owing to the indecisiveness of Lord Mayor of London Sir Thomas Bloodworth. By the time large-scale demolitions were ordered on Sunday night, the wind had already fanned the bakery fire into a firestorm that defeated such measures. The fire pushed north on Monday into the heart of the City.

Order in the streets broke down as rumours arose of suspicious foreigners setting fires. The fears of the homeless focused on the French and Dutch, England's enemies in the ongoing Second Anglo-Dutch War; these substantial immigrant groups became victims of lynchings and street violence. On Tuesday, the fire spread over most of the City, destroying St Paul's Cathedral and leaping the River Fleet to threaten King Charles II's court at Whitehall. Coordinated firefighting efforts were simultaneously mobilising; the battle to quench the fire is considered to have been won by two factors: the strong east winds died down, and the Tower of London garrison used gunpowder to create effective firebreaks to halt further spread eastward...

The social and economic problems created by the disaster were overwhelming. Evacuation from London and resettlement elsewhere were strongly encouraged by Charles II, who feared a London rebellion amongst the dispossessed refugees. Despite several radical proposals, London was reconstructed on essentially the same street plan used before the fire...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Fire_of_London